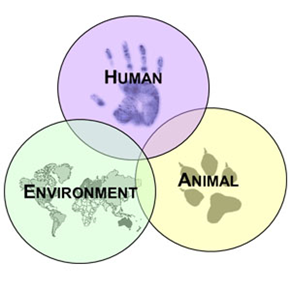

One Health is the integrative effort of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally, and globally to attain optimal health for people, animals, and the environment.

Essentially One Health means that all life is connected (and interdependent). Though the phrase has been used in scientific literature for 10 years, the notion of One Health is not new. The concept echoes the writings of ancient philosophers. As early as c.460-c.377 B.C., Hippocrates wrote that human health depends on the environment in his book On Airs, Waters, and Places.

The One Health concept has the potential to represent a paradigm shift that leads to a wider and deeper commitment to interdisciplinary action addressing the protection of human and animal health as well as sustainable environmental practices in the 21st century. However, when we consider the major challenges facing the planet, particularly in terms of the overuse of antibiotics and transmission of zoonotic diseases, care is required in order to avoid taking an exclusively anthropocentric view. In stark contrast to the estimated 7 billion humans living on the planet, current estimates of total livestock species including cattle, small ruminants (sheep/goats), pigs and poultry amount to a staggering 24 billion animals.

Recently, the FAO has teamed up with the WHO and the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) in a global strategic plan to achieve food and health security by strengthening veterinary and animal production systems so they can better monitor disease threats and care for the health of livestock and the environments they are raised in. FAO estimates suggest that surveillance and response in animal hosts can reduce the costs associated with zoonotic disease outbreaks by 90%. Therefore key to delivery on One Health initiatives is controlling disease at source and earlier and more effective intervention strategies require a much more detailed understanding of livestock immunity. A major potential strength in One Health partnerships is the ability to leverage the more established human immunology expertise toward tackling recalcitrant problems in the livestock sector. Effective One Health partnerships will help identify new biomarkers for disease diagnosis, shed light in the complex interactions between the immune system and nutrition - thereby identifying mechanisms to bolster immunity without antibiotics, and help uncover the evolutionary differences between species that could form the basis for rational design of next generation vaccines in livestock.

Manhattan Principles of One Health:

Essentially One Health means that all life is connected (and interdependent). Though the phrase has been used in scientific literature for 10 years, the notion of One Health is not new. The concept echoes the writings of ancient philosophers. As early as c.460-c.377 B.C., Hippocrates wrote that human health depends on the environment in his book On Airs, Waters, and Places.

The One Health concept has the potential to represent a paradigm shift that leads to a wider and deeper commitment to interdisciplinary action addressing the protection of human and animal health as well as sustainable environmental practices in the 21st century. However, when we consider the major challenges facing the planet, particularly in terms of the overuse of antibiotics and transmission of zoonotic diseases, care is required in order to avoid taking an exclusively anthropocentric view. In stark contrast to the estimated 7 billion humans living on the planet, current estimates of total livestock species including cattle, small ruminants (sheep/goats), pigs and poultry amount to a staggering 24 billion animals.

Recently, the FAO has teamed up with the WHO and the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) in a global strategic plan to achieve food and health security by strengthening veterinary and animal production systems so they can better monitor disease threats and care for the health of livestock and the environments they are raised in. FAO estimates suggest that surveillance and response in animal hosts can reduce the costs associated with zoonotic disease outbreaks by 90%. Therefore key to delivery on One Health initiatives is controlling disease at source and earlier and more effective intervention strategies require a much more detailed understanding of livestock immunity. A major potential strength in One Health partnerships is the ability to leverage the more established human immunology expertise toward tackling recalcitrant problems in the livestock sector. Effective One Health partnerships will help identify new biomarkers for disease diagnosis, shed light in the complex interactions between the immune system and nutrition - thereby identifying mechanisms to bolster immunity without antibiotics, and help uncover the evolutionary differences between species that could form the basis for rational design of next generation vaccines in livestock.

Manhattan Principles of One Health:

- 1. Recognize the essential link between human, domestic animal and wildlife health and the threat disease poses to people, their food supplies and economies, and the biodiversity essential to maintaining the healthy environments and functioning ecosystems we all require.

- 2. Recognize that decisions regarding land and water use have real implications for health. Alterations in the resilience of ecosystems and shifts in patterns of disease emergence and spread manifest themselves when we fail to recognize this relationship.

- 3. Include wildlife health science as an essential component of global disease prevention, surveillance, monitoring, control and mitigation.

- 4. Recognize that human health programs can greatly contribute to conservation efforts.

- 5. Devise adaptive, holistic and forward-looking approaches to the prevention, surveillance, monitoring, control and mitigation of emerging and resurging diseases that take the complex interconnections among species into full account.

- 6. Seek opportunities to fully integrate biodiversity conservation perspectives and human needs (including those related to domestic animal health) when developing solutions to infectious disease threats.

- 7. Reduce the demand for and better regulate the international live wildlife and bushmeat trade not only to protect wildlife populations but to lessen the risks of disease movement, cross-species transmission, and the development of novel pathogen-host relationships. The costs of this worldwide trade in terms of impacts on public health, agriculture and conservation are enormous, and the global community must address this trade as the real threat it is to global socioeconomic security.

- 8. Restrict the mass culling of free-ranging wildlife species for disease control to situations where there is a multidisciplinary, international scientific consensus that a wildlife population poses an urgent, significant threat to human health, food security, or wildlife health more broadly.

- 9. Increase investment in the global human and animal health infrastructure commensurate with the serious nature of emerging and resurging disease threats to people, domestic animals and wildlife. Enhanced capacity for global human and animal health surveillance and for clear, timely information-sharing (that takes language barriers into account) can only help improve coordination of responses among governmental and nongovernmental agencies, public and animal health institutions, vaccine / pharmaceutical manufacturers, and other stakeholders.

- 10. Form collaborative relationships among governments, local people, and the private and public (i.e.- non-profit) sectors to meet the challenges of global health and biodiversity conservation.

- 11. Provide adequate resources and support for global wildlife health surveillance networks that exchange disease information with the public health and agricultural animal health communities as part of early warning systems for the emergence and resurgence of disease threats.

- 12. Invest in educating and raising awareness among the world’s people and in influencing the policy process to increase recognition that we must better understand the relationships between health and ecosystem integrity to succeed in improving prospects for a healthier planet.

UCD and One Health - and the relevance of agriculture

|

UCD is in the ideal position to lead in One Health initiatives as all of UCD’s health professionals already exist under one banner (UCD college of Health and Agricultural Sciences and UCD Conway) providing an exciting opportunity to exploit synergies which exist across the One Health spectrum.

UCD practical One Health actions:

If you haven't realised it yet, the role of agriculture (and future agricultural scientists) to the delivery on One Health is front, core and centre. Environmental degradation exposes us all to new threats from climate impacts, food sustainability and exposure to infectious diseases. Agriculture also offers many solutions in terms of our expertise in environmental remediation and restoration, biodiversity and habitat protection. In conjunction, our plant and animal agri-innovation provides technological solutions to the big issues we are grappling with in terms of food supply, traceability and food quality. In terms of animal health, tackling infectious disease at source - in livestock and in wildlife populations prevents spreading negative impacts on farm, as well as protecting the food chain and human health. One often overlooked way in which agriculture can also provide solutions is that through our study of animals, alternative solutions to infectious diseases can be identified and novel immunotherapies exploiting these evolutionary solutions can be used in animal and human medicine. It is also critically important to recognise that One Health approaches can have a particularly visible impact in developing countries where the connection between farming and the environment and human health can often be more visible. A framework that includes all stakeholders in any development from education through agriculture and to human health will be best positioned for success and can have a dramatic effect on poverty levels. |

You and One HealthRelevant literature on One Health, including pandemics, case studies and blueprints to evaluate the effectiveness of One Health approaches.

Concrete examples of One Health research in UCD - on TB, Fertility and Water quality |

|

Join the UCD One Health society - see link

|

If you are in any doubt about the urgency of One Health

|

The cupboard is now dry: Dame Sally Claire Davies - a British physician was the Chief Medical Officer for England, and the Chief Scientific Adviser at the Department of Health explains the impact of disease on human health. Essential viewing!

Also Dr Delia Grace form ILRI, Africa talking about zoonotic diseases on the rise. |

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by Letshost.ie